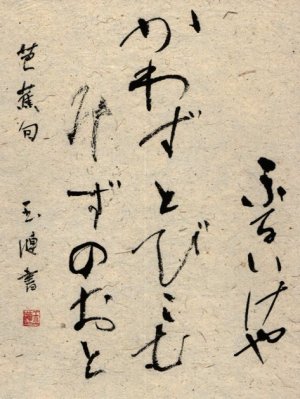

an old pond—

the sound of a frog jumping

into water

– Matsuo Basho

Haiku is the most well-known of the Japanese poetic styles. The beauty of it lies in its simplicity and limitations. In three lines totalling seventeen syllables, the poet conveys the mood of a scene based on several strict rules. These syllables are often divided into groups of five, seven, and five. Within these lines exists a wealth of meaning of one moment, frozen in time to be reflected upon.

Haiku grew out of hokku, the opening lines of the longer linked verse form called renga. The opening verses often set the tone for the rest of the poem. Lighter, less courtly versions of these linked verses called haikai no renga soon became popular with the masses. These usually portrayed everyday life in a humorous way, using wordplay and allusions to enliven the limited words. In the 16th century Matsuo Basho became well known as a master of this artform. His collections of poetry contained polished gems of profound depth, as he wielded the words to speak not only of a scene, but invoke emotions of happiness, compassion and despair. It was Masaoka Shiki in the 19th century who first took these three lines and established them to be appreciated independently. These days free-form haiku deal with a range of topics that goes beyond the seasons – the city, trains, the falling rain and technology – and yet they remain full of the same spirit as those made by the masters.

Because of the limited number of syllables haiku writers use certain poetic phrases to represent a season or idea. The moon, the mists, even the sound of water can represent the vibrant spring or the solitude of autumn. Often two of the lines will contain a complete thought, while the remaining line points the reader back to the reality enclosed in its words. Every reader sees a haiku differently, caught by what they see and interpret in these words.

[tags]haiku, japan, Matsuo Basho[/tags]